(Source: Flickr)

How to Make Sauerkraut

Do you love sauerkraut? Whether you say yes or no, you’re not alone. Assertively-flavored, sour-savory sauerkraut is one of those foods that people seemingly either love or despise; few people seem to take the middle ground. For a long time, I was part of the latter group. I didn’t like the look, smell, or taste of sauerkraut, and I felt like it was a travesty to wreck a perfectly good hot dog with the stuff.

But then, one day, I tried a homemade version of sauerkraut, served alongside a kielbasa platter. It was homemade, studded with caraway seeds and with a crisp texture. This sauerkraut was like an epiphany to my taste buds. It was the perfect acidic complement to the kielbasa, acting as a flavor complement and a palate cleanser to the unctuous, rich meat. Suddenly, I understood sauerkraut, and I wanted more. All it took was a well executed version of this fermented food to make me a believer.

(Source:Flickr)

What is sauerkraut?

Most people have at least a passing knowledge of the stuff, even if it’s only to conjure an image of shredded white stuff on top of a hot dog. But for many, that’s where the knowledge ends. So let’s back up for a moment to explore: what is sauerkraut, exactly?

The short version? Pickled cabbage.

The long version? To make sauerkraut, cabbage is shredded, generously salted, sometimes along with vinegar, water, or other seasonings, and left to ferment for as short as a few days, or as long as a month. The salt is the miracle worker here: it naturally extracts the moisture from the cabbage, forming a sort of brine. The cabbage ferments in the mixture, and during this time, “good” bacteria produces lactic acid, which helps aid the conversion of the cabbage into sauerkraut. Through this process, the enzymes break down, making the molecules smaller and more easily digestible.

Sauerkraut is part of a long tradition of food fermentation. Fermented foods themselves have been kicking around for quite some time: there is evidence that fermented drinks were being produced in Babylon as long as 7,000 years ago. China is largely viewed as the birthplace of fermented vegetables; it is here that pickled cabbage was developed into an everyday food. As early as the year 200 B.C, Chinese cooks were pickling cabbage, likely in rice wine, and using it as part of their meals. Eventually, via Ghengis Khan, the dish made its way to Europe. It became particularly popular in Germanic countries, and is still strongly associated with German (or in the U.S., Pennsylvania Dutch) cuisine.

Benefits of sauerkraut

In recent years, fermented foods have gotten plenty of press for their health benefits. So what positive effects can you expect if you eat sauerkraut? Here are just a few of the many benefits:

Improved digestion: Sauerkraut is very good for digestion. As previously noted, during the fermenting process, the molecules of the cabbage shrink, making sauerkraut much easier to digest than raw cabbage. Easier digestion means easier elimination, which is key to overall health.

Probiotic power: The “good” bacteria present in sauerkraut can feed on leftover digestive waste, improving overall health by cleansing unnecessary waste. In this way, eating sauerkraut can be a proactive measure in preventing disease, and boosting the immune system for overall health.

A diet-friendly food: Sauerkraut will fill you up without filling you out: it is naturally low in calories (about 30 calories per cup), and is naturally high in fiber and low in cholesterol.

Vitamins and minerals: Sauerkraut is considered a good source of calcium and magnesium, and a very good source of vitamin C, vitamin K, vitamin B6, folate, iron, potassium, copper, and manganese.

(Source: Flickr)

Making sauerkraut

Sauerkraut’s health benefits are at their most powerful when it is homemade. Happily, making your own sauerkraut is simple: it requires minimal ingredients, and can even be made in a mason jar.

The process is fairly simple: combine cabbage, salt, and seasonings of your choice, and let them ferment. Supplies are likewise quite minimal: you’ll need a clean, large container to allow the cabbage to ferment (a glass jar is fine if you don’t have a fermentation crock like the one pictured above), a few clean kitchen towels, and non-aluminum utensils (they can discourage the fermenting process).

As long as you are working with clean supplies, the pitfalls are quite minimal. All you need is a little time to let the cabbage ferment!

Recipe: Homemade Sauerkraut

Adapted from The Old Farmer’s Almanac

Makes 2 quarts

1 gallon container (such as a large, 1 gallon jar like restaurants use for storing pickles)

- clean kitchen towels, for covering

- a wooden spoon or non-aluminum potato masher

- 5 pounds cabbage

- 3 tablespoons kosher salt

Procedure

- Shred your cabbage to fine slivers. Alternate layers of cabbage with a sprinkle of salt, tapping the mixture down with a wooden spoon or potato masher to slightly flatten the mixture. Finish with salt on the top. You might be feeling like sauerkraut seems like a faraway goal right now, but I promise, it’s going to happen.

- Cover the mixture with a towel secured to the vessel with string or a rubber band. Do not seal it airtight.

- Press the mixture with a spoon or non-aluminum potato ricer every few hours, but otherwise let the mixture sit at room temperature (65 to 75 degrees is ideal), away from direct sunlight, for a day. Chances are, enough brine has formed that it covers the cabbage. If not, help the mixture along by adding 1 ½ teaspoons of salt to 1 cup of water, and add only enough so that the cabbage is fully submerged. Once again, cover and let sit.

- After a few days, a white frothy coating will form on the top of the mixture. Skim it off, and replace the towel cover with a new one to discourage “bad” bacteria from forming. Repeat this process daily as long as the white frothy coating keeps on forming. When the bubbles stop, your fermenting process is done! This can take up to a few weeks.

- Transfer to jars for storage, retaining the brine so that even if divided, each portion remains submerged in brine.

Storing / packaging your homemade sauerkraut

Keep the sauerkraut in its own brine, which acts as a natural preservative. Store the finished sauerkraut in the refrigerator (approximately 40 to 50 degrees F), in its own brine. Do not freeze.

What can you do with homemade sauerkraut?

Now that you’ve made sauerkraut, show it off in one of these delicious ways.

Make a cake: did you know that sauerkraut can be used to create a delicious chocolate cake? It might sound strange, but one bite will convince you that it’s a very good combination.

(Source: Flickr)

Serve it with sausage: Rich meats such as kielbasa or bratwurst work wonderfully with a side of sauerkraut. The sour, biting nature of the sauerkraut works as the perfect complement to rich meats.

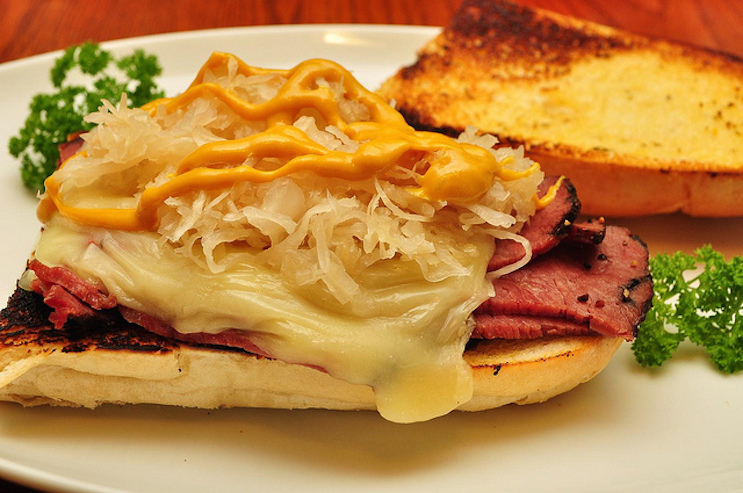

(Source: Flickr)

Make it extra flavorful with caraway seeds: You can add caraway seeds to taste (1 tablespoon is a good starting point) either during step 1 in the recipe, or after it has fermented. It really adds a new dimension to the flavor!

Do you like sauerkraut?